A Curious Implementation of Copper-Plate Printing

/Here’s a nifty permutation of copper-plate printing that was quite new to me. I encountered it among the teaching materials in the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia; I had asked for it sight-unseen, as a possibly useful work to show the students in the first course I have taught at RBS. (RBS has given permission for me to use the images I took with the iPhone in this blog.) Now that I’ve studied this work in person, I’ll be sure to use it in future incarnations of the course!

The map was a “post-map” showing the roads of Germany:

Johann Jacob von Bors, Neue und vollständige Postkarte durch ganz Deutschland / Nouvelle carte geographique des postes d’Allemagne, posthumously edited by Franz Joseph Heger (Nuremberg: Homann Heirs, 1764)

See Neumann (2019) for more on the phenomenon of post maps in Germany. The Bibliothèque nationale de France has one assembled into a large map …

… although this might be a later variant published after 1764. (In addition to the two scales below the title cartouche at lower-left, there’s a third, simple scale squeezed in below the title.) Dealers have recorded a 1784 variant with the individual sheets housed in a leather case or in marbled-paper wrappers. The dealers want to call this work a “wall map” because of its size, but it seems not to have been intended to be mounted on a wall (see Brückner 2019).

Rather, we can see from the RBS impression that the map was actually intended to be bound as a small atlas or pasted onto cloth for folding down. The RBS atlas was bound in stiff cardboard wrapped in colored paper, and with a manuscript title on the cover, in English:

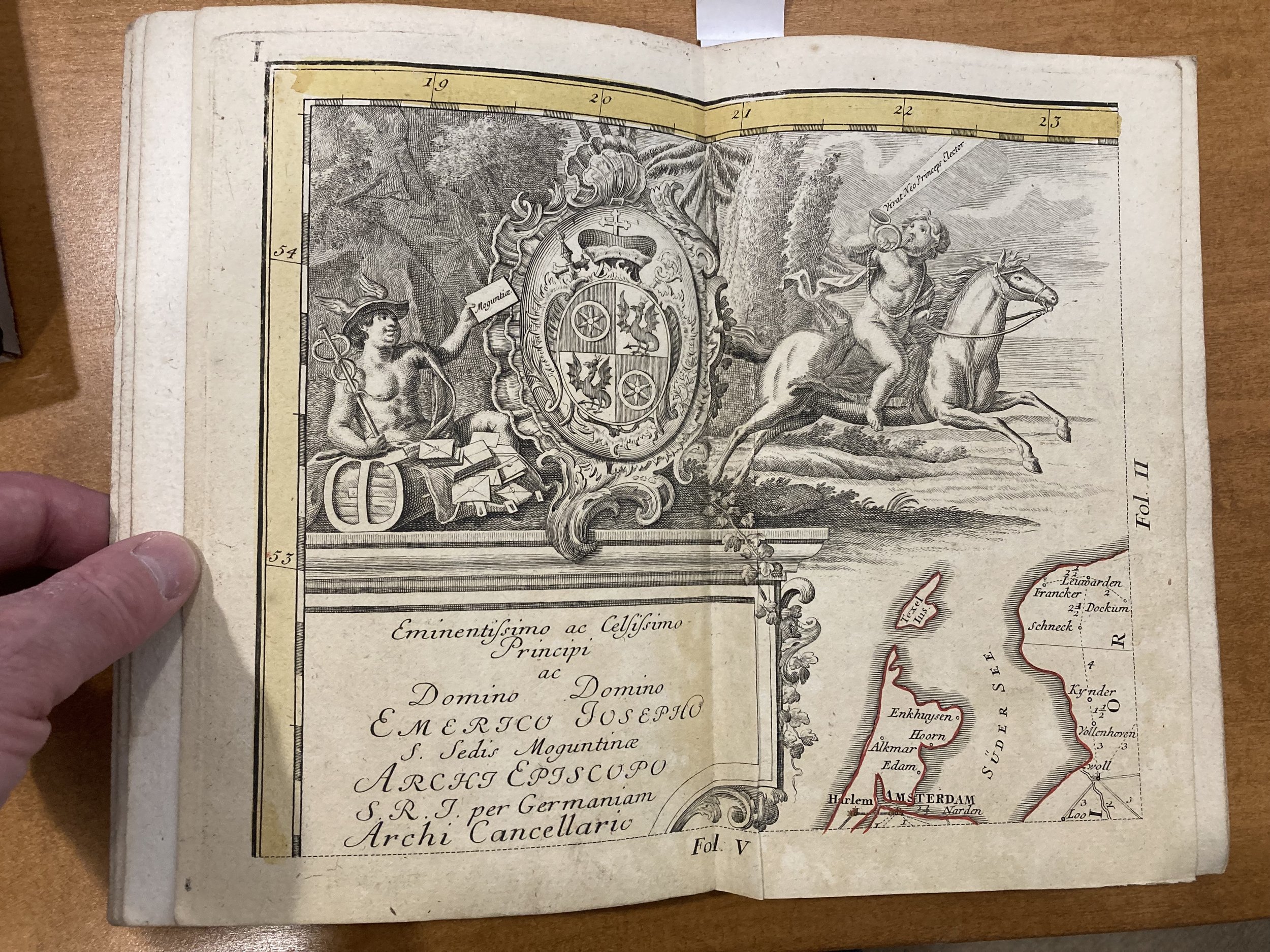

It also has a small index map at the front:

Across the bottom of the page are the instructions to the binder:

Bericht an den Buchbinder. Wann man die 16. Felder der grossen Postkarte nicht in eine Karte zusam[m]en fügen, sondern gebunden bey sich führen will, so wird dieses kleine Kärtgen voran, und die 16. Felder nach ihren oben lincker Hand befindlichen Numern hintereinander gebunden. Nürnberg, zu finden bey denen Homännischen Erben, 1764.

Instructions to the bookbinder. If you do not want to assemble the 16 sheets of the large postmap together into one map, but want to keep them bound, then this small map is to be placed first, and the 16 sheets are bound one after the other according to their numbers in the upper left hand. Nuremberg, sold by [to be found at] the Homman Heirs, 1764.

So far, so normal. The interesting part is the evidence of the plate marks on the index map and on the 16 sheets of the atlas.

Note: plate marks are a physical deformation of the paper as it is forced down over a copper plate in a high-pressure rolling press. The high pressure is needed to force the (damp) paper into the lines engraved or etched into the copper plated (heated for printing) in order to pick up the ink. Plate marks can be felt and, if the surface of a plate is inadequately cleaned between inking and printing, by the collection of ink.

In all of the small, pocket-sized atlases I’ve seen, each sheet was printed from its own copper plate; the impression on each sheet is therefore surrounded by a plate mark. But in looking at this postmap-atlas, I was immediately struck by the odd pattern of plate marks on the separate sheets. Here’s sheet one, bearing the dedication:

The plate mark is plainly evident only across the top and down the left side of the impression. There is, at top left, a curved corner expressing the corner of the printing plate:

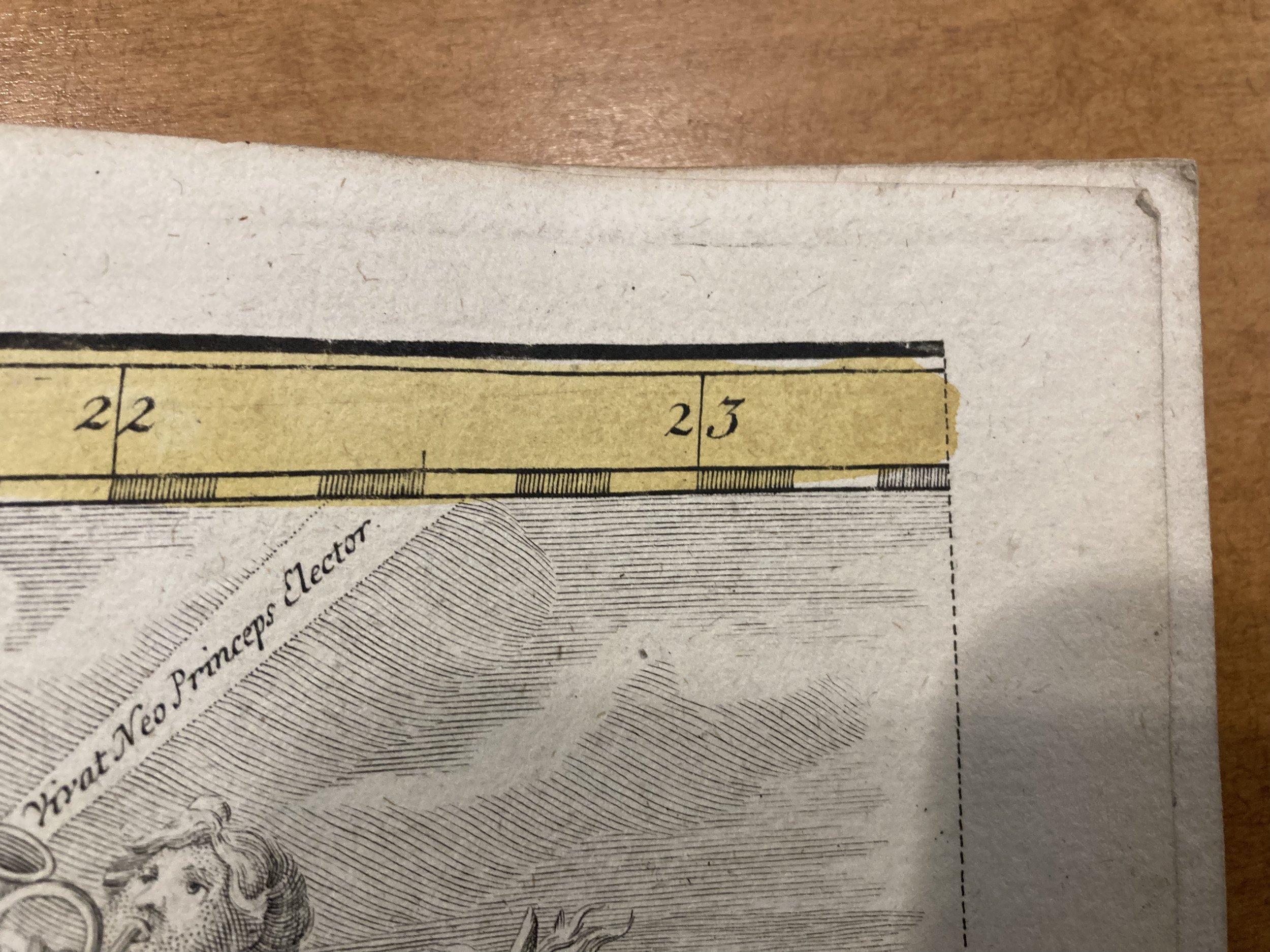

The thing is, the plate mark does not continue around the other edges. Sheet 2, to the right, has only a plate mark across the top of the impression. Here’s a detail of the upper-right corner of the sheet, with the sole plate mark running off the edge of the paper:

The next rounded corners of the plate mark are found only on sheets 4 (upper right), 13 (lower left), and 16 (lower right). The last can be seen here:

The four interior sheets have no plate marks at all; nor, for that matter does the index sheet. What all this implies is that all sixteen sheets were printed from the one, large printing plate:

Diagram of the postmap’s 16 sheets engraved on a single plate.

That is, the entire map was pulled as a single impression from the printing plate, them the page trimmed into sixteen equal pieces, leaving a margin around each impression, for binding into the pocket atlas. Alternatively, the individual pieces might be trimmed tightly for assembly into a single map (as the BnF impression, above).

This strategy strikes me as a wonderful way to cut down on printing time and thereby reduce the unit cost of the map, while permitting the map to be sold in two handy formats (atlas or dissected onto cloth).

Anyone know of a similar implementation of copper-plate printing???

Reference

Brückner, Martin. 2019. “Wall Map.” In Cartography in the European Enlightenment, edited by Matthew H. Edney, and Mary S. Pedley, 1636–38. Vol. 4 of The History of Cartography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Neumann, Joachim. 2019. “Thematic Mapping in Germany.” In Cartography in the European Enlightenment, edited by Matthew H. Edney, and Mary S. Pedley, 1373–77. Vol. 4 of The History of Cartography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.